In yesterday’s post I sketched out some high-concept stuff about Godsbarrow, and having finished Worlds Without Number‘s “The World” steps I’m moving on to “The Region” — the slice of Dormiir called the Unlucky Isles.

As with the first Dormiir post, large portions of this one are pretty raw — more or less straight from the Notepad file I’ve been massaging and into WordPress. (I’ve learned that if I obsess over polish at this stage of worldbuilding, I get bogged down and never get much further. The raw fire of creativity is where it’s at!)

The Unlucky Isles

Name the region.

The Unlucky Isles, so named because the god Slljrrn (“SULL-jern”) died here, sinking into the sea and cursing this scattering of islands — and because the isles draw the ill-fated like moths to a flame.

An aside: names

Before I tuck into the next step, there’s some advice about names in WWN that I love and want to share here:

Conventional fantasy names tend to be random nonsense-syllables picked from the creator’s cultural phoneme stock, and places often end up as the city of AdjectiveNoun or the NounNoun river. While some of this can work perfectly well, it’s easier for the GM to pick some obscure or extinct real-world language known to nobody at the table and use it for names. Even if the words they use from it have no relation to what they’re naming, the consistent set of sounds and syllable patterns will help give a coherent feel to the work.

Worlds Without Number, p.119

That tracks with languages in Star Wars, which are (or were, anyway) often real-world languages not likely to be familiar to a primarily English-speaking audience; I’ve always thought that was a fun approach.

I decided to stick to dead languages. Palaeolexicon offers dictionaries of long-dead languages, and browsing through them was a lot of fun. In coming up with names, I used dead languages where it felt right, and made up my own bullshit everywhere else (because I do enjoy making up my own bullshit).

That shook out to dead languages for some names associated with three nations — Etruscan for Brundir, Proto-Turkic for Ahlsheyan, and Thracian for Yealmark — and made-up stuff for the other three.

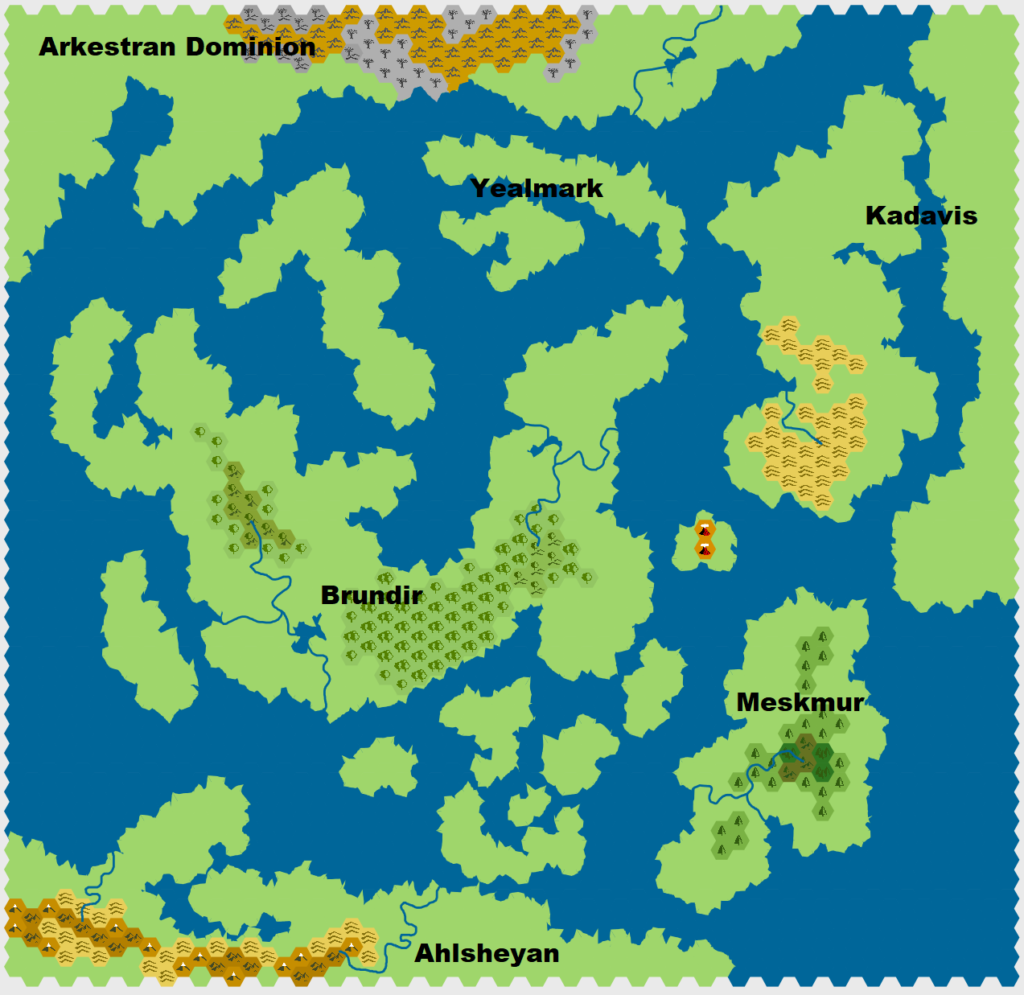

Choose about six major geographical features.

Before this step, I started working on my map. I used Worldspinner to cycle through arrangements of continents until I found one that pleased me, and then switched to Worldographer Pro to build my hex map. (I’ve been using Hexographer, its predecessor, for almost a decade; both are excellent, and both offer robust free versions.) I can’t think too much about a fictional place without a map of it, so I’m jumping ahead a bit, WWN-wise.

Armed with my landform map, I jotted down my major geographical features, adding them to the map as I went:

- Ulscarp Mountains, a range of jagged, snowcapped peaks in Ahlsheyan

- Vykus and Vnissk, the twin volcanoes of Deathsmoke Isle

- The Ockwood, a vast, dense forest in Brundir

- Sculn Hills, a rocky region on the island of Rasu Miar, in Kadavis

- Atrachian Wastes, a region of badlands and dead forest in the Arkestran Dominion

- The Vorga Forest, light evergreen woods that dot Meskmur

This step necessarily bled into the next couple, as kingdoms, gods, and other elements of the setting popped into my head, were iterated upon, and got plugged into the other region-creation steps.

Create six nations or groups of importance.

Brundir (“BRUNN-dihr”), the largest and most central of the Unlucky Isles. Brundir is rich in natural resources, including timber and arable land, and boasts a coastline full of protected bays. Brundir is a mercantile power with a large and powerful navy. It’s also a haunted place and a breeding ground for strange creatures, thanks to Slljrrn’s lingering essence, and Brundirans tend to have a pessimistic streak.

Arkestran Dominion (“arr-KESS-trun”), stretching off the map to the north. A militaristic, expansionist elven nation, the Dominion sits atop an entire pantheon of dreaming gods and makes extensive use of the Wraithsea to exert their influence across Dormiir. The southern reaches, however, are lightly populated hinterlands dominated by the inhospitable Atrachian Wastes; the Dominion’s main focus is to the north…for now.

Meskmur (“MEHSK-murr”), a small kingdom of sorcerers on the southernmost edge of the Unlucky Isles, is a secretive, isolated place. By and large, the Meskmuri stay out of the politics of the Isles, and so Meskmur serves as the de facto “neutral ground” for moots, summits, and other gatherings (collecting payment and tribute in exchange). Temples and shrines to Jiur and Sarrow, the Red Twins central to Meskmuri faith, dot the island.

Ahlsheyan (“ahl-SHAY-ahn”), a chilly, windswept dwarven kingdom which abuts the Unlucky Isles to the south. Ahl dwarves are equally at home deep underground and plying the waves. The three pillars of Ahl society are wind, waves, and stone (representing impermanence, opportunity, and the past, respectively), and Ahl relationships are often tripartite (polycules, business ventures, etc.). Ahl “wind sculptures” — made of stone shaped so as to change in interesting ways as they are worn away by wind and weather, and not sold or exhibited until decades after they were first made — are famous throughout Godsbarrow.

Kadavis (“kuh-DAVV-iss”), in the east, is notorious for the raiders who populate Rasu Miar (“ill-fated land” in Kadavan), the island that marks its westernmost territory. Between the rocky Sculn Hills and the pall of smoke emanating from Deathsmoke Isle, Rasu Miar is a harsh place; outcasts, exiles, and wanderers who don’t fit into Kadavan society often find their way here. Kadavis itself is a prosperous, decadent kingdom composed of dozens of squabbling fiefdoms. Kadavan culture places great value on ostentatious displays of wealth and glory.

Yealmark (“YALL-mahrk”) consists of two small islands wedged between the Dominion to the north, Kadavis to the east, and Brundir to the south, and is the youngest kingdom in the Unlucky Isles. Formerly part of Brundir, Yealmark was granted to the Nuav Free Spears, a large mercenary company, some thirty years ago as payment for a contract. The Free Spears are disciplined in battle but run wild between contracts, so Yealmark is a strange mix of organized martial society and raucous revelry, and attracts more than its share of pirates, ne’er-do-wells, and adventurers as a result.

Identify regionally-significant gods.

- Brundir — θana (“THAH-nah,” the forest; the versatility of trees) and σethra (“SHETH-ruh,” good fortune), commonly referred to as the Mast and the Sail (the strong, well-made foundation that enables you to catch the winds of good fortune, taking you away from the ill luck of the Isles).

- Etruscan is my source for some Brundiran names, including special characters like Sigma and Theta (used above).

- Arkestran Dominion — Taur Kon Drukh, the Ceaseless Flame, who burns away the threads of fate woven by other gods, and soothes the slumber of the old pantheon (ensuring the Arkestrans don’t lose access to the Wraithsea).

- Meskmur — Jiur and Sarrow (“JEE-oor” and “SAH-row”, the Red Twins, believed to live inside the volcanoes Vykus (Jiur) and Vnissk (Sarrow) on Deathsmoke Isle, and venerated in large part to keep them there — and away from Meskmur itself (ditto the smoke, which most often drifts north instead of south, fouling the air over Rasu Miar).

- Ahlsheyan — Kōm (“COMB,” wind, impermanence), Ebren (“EHB-run,” waves, opportunity), and Iāka (“ee-YAY-kuh,” stone, the past) are the cornerstones of Ahl faith and society.

- Proto-Turkic is my source for some Ahl names.

- Kadavis — Iskuldra, the Golden Mask (“iss-KUHL-druh,” wealth, glory, recognition), principal deity in a pantheon that includes over 200 “small gods” (other aspects of prosperity, commerce, fashion, etc.) who are venerated in its many fiefdoms.

- Yealmark — Pays obeisance to Brundir’s principal gods, θana and σethra, but also to Bruzas (“BROO-zoss”), the god of blood and revelry from their original homeland, Nuav (whose symbol is a blood-filled golden bowl).

- Thracian is my source for some Yealmark names.

Many islefolk also pray to Nsslk (“NUH-sulk”), son of long-dead Slljrrn, who sleeps beneath the waves in the Unlucky Isles, in the hope that their prayers will keep him from dying — and thereby further cursing the Isles.

Make a sketch map of the region.

Mapping advice is scattered around the worldbuilding chapter, and doesn’t perfectly match the book’s setting, so I did some head-scratching and came to my own conclusions. WWN recommends a square 200 miles on a side, with 6-mile hexes, for the region map — but the example in the book is more like 300 miles x 360 miles, and I liked its size. So I went with 60 hexes by 50 hexes (widescreen monitor-shaped, not book page-shaped), for a regional area of 108,000 square miles.

That would make the Unlucky Isles the eighth-largest US state by area, and roughly the size of Colorado, Nevada, or Arizona.

WWN notes that rivers and (optionally) large lakes/inland seas come next, and to make logical rivers I needed to add some mountains and hills to my extant map (and fiddle with some of the existing features, too). That plus country labels gave me the map I used to open this post:

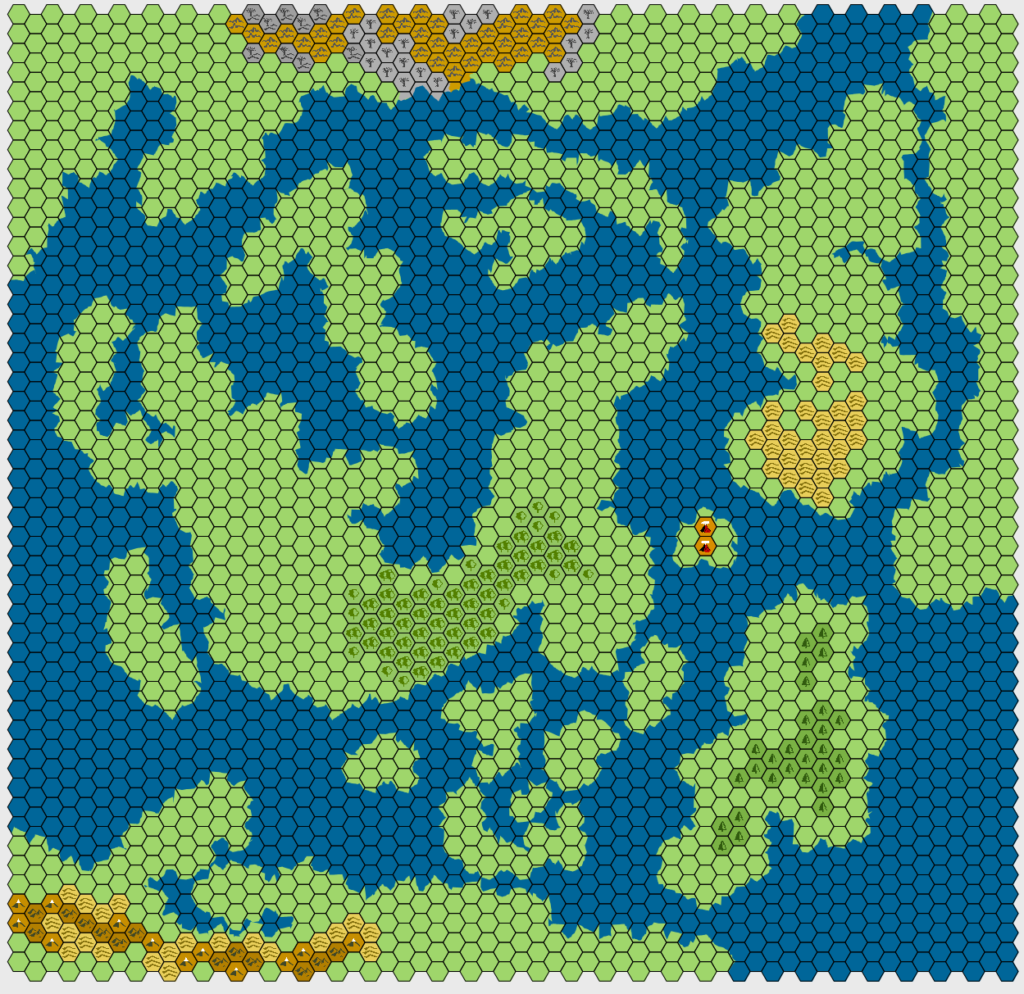

Worldographer has a really cool feature called Child Maps that auto-generates a version of your current map on a different scale, with a number of hexes per parent-map hex that you determine. For example, I can take the Unlucky Isles at World level and step down to Continent level with 6 hexes per hex, and Worldographer will spit out that massive map.

WWN’s process doesn’t have you adding cities and other features to your kingdom-level map, but major features do appear on its example map. I want to see more detail than I currently have on my region map (at 6 miles/hex), so my next step will be to add cities and features to this map. (If I were about to start a campaign, I’d probably set it in a central region of Brundir, generate a 6-hexes-per-hex child map, and add villages, caves, dungeons, ruins, and so forth to those 1-mile hexes.)

I’ll do that as part of answering the three remaining WWN questions about the region — and in another post, as this one’s already massive!

(This post is one of a series about worldbuilding with Worlds Without Number.)